Agricultural supply chains have become increasingly complex and for those serving discerning markets, increasingly demanding. Product integrity, safety, and quality attributes are moving from being based on reassurances to evidence and audit.

In the past, a handshake, a solid conversation, a trusted voice on the phone would have provided the necessary confidence and trust in the supply chain. At our local farmers’ market, where buyers meet suppliers directly, inspect the wares, and are invited to visit the farm at leisure, this trust still exists.

Global supply chains however, transcend country boundaries, time-zones, and cultures, so the elements of local trust must be replaced by contracts, standard processes, and hard data. Faced with these new demands, how will the “data infrastructure” of the typical livestock farm respond?

In our discussions with farmers, advisors and processors we’ve identified several spheres of relationship where farm data needs to be exchanged between people and tools. In the past some of these exchanges were verbal, or maybe used paper or fax. While the data used in each of the three examples below are superficially similar, the uses, aggregation, and controls on that information are quite different.

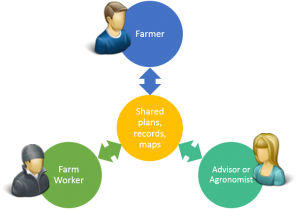

Farm decision making

Data leveraged for farm decision making may be hosted in crop and agronomic systems, embedded devices and control systems, or in veterinary and livestock management systems. Data is typically shared between farmer, farm workers, and advisors – the latter including agronomists, veterinarians, and fertiliser advisors and other farm consultants.

Data leveraged for farm decision making may be hosted in crop and agronomic systems, embedded devices and control systems, or in veterinary and livestock management systems. Data is typically shared between farmer, farm workers, and advisors – the latter including agronomists, veterinarians, and fertiliser advisors and other farm consultants.

Previous generations of such systems were typically operated by one party, with printed reports and documents produced for others. We’re now seeing the adoption of cloud-based systems that provide controlled levels of visibility and access for various roles in the farm business.

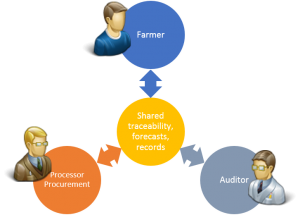

Supply planning and tracing

A different set of interactions for some of the same data occurs when we consider the purchasing functions of the primary processor. Here interactions focus on predicting livestock supply and negotiating commitments, tracing the provenance and welfare of animals and other functions necessary to provide an auditable supply programme.

Information about the quality and performance of product (meat, milk, grain) may be returned from the processor to the farmer.

Interactions at this level could build from the same data; but in practice this is still evolving. Levels of trust are often different too, especially if there has been a history of adversarial relationships, as farmers and processors both fear that openness on their part may be abused. The challenge is to define appropriate levels of visibility, aggregation and control over data. Systems that are hosted by independent third-parties with contracts to protect data may be more acceptable to some participants.

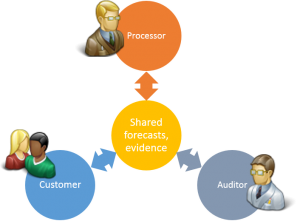

Supporting value-added relationships

Information gathered from farm, auditor, and processor relationships has its place elsewhere in the supply chain. Information about the provenance of product (farms of origin and their practices) increases confidence and may even provide the “story” that differentiates the product in the market.

Information gathered from farm, auditor, and processor relationships has its place elsewhere in the supply chain. Information about the provenance of product (farms of origin and their practices) increases confidence and may even provide the “story” that differentiates the product in the market.

Forecasts from farms help processors and their customers negotiate appropriate supply contracts that match demand and supply. Evidence from auditors’ inspection of farms and their records is essential for supply chain compliance.

This rich data conversation only exists in a few niche examples at present. For the most part, negotiations around supply and demand are taken with parties protecting their own cards, and supply chain audit records rely on separate forms and data collection. The opportunity exists however to leverage data right along the supply chain, and if this is undertaken with care and responsibility, all members of the supply chain will benefit.